the catalysts to knowledge: The Basics of Spectroscopy

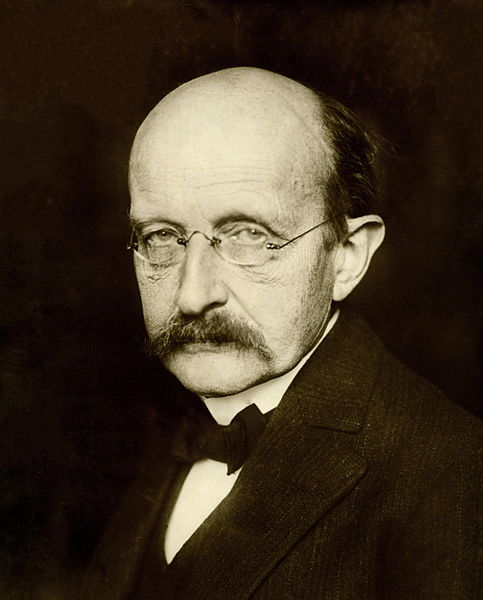

Joseph von Fraunhofer

Joseph von Fraunhofer (6 March 1787 - 7 June 1826) was an optical lens manufacturer and not an astronomer. His lens making abilities were carefully honed under the watchful eye of Pierre Guinand, but he soon surpassed him in knowledge, ability and craftsmanship.

The story of Fraunhofer is an inspiring one. He picked himself up by the bootstraps to become a formidable contributor to the scientific pursuits of his time. But the inspiration is not due to his rags to riches story, for that pales, in comparison to the account of his impact on the then burgeoning science of Spectroscopy. His application of maximal effort in one field - lens making - led to remarkable insights and discoveries in the world of physics. Not many individuals in history can match such a record of diligent exertion. And even less can do so with humility and grace.

When sunlight is passed through a prism it generates a continuous rainbow-like spectrum, yet this spectrum is made up of more than just the colours of the rainbow, it also has dark gaps of various widths throughout. These gaps were first spotted by and English scientist William Hyde Wollaston (6 August 1766 - 22 December 1828) in 1802. He had been studying the refraction (how much light waves bend when they go from one medium to another - in this case from air to a glass prism), of sunlight. The method of the experiment was to shine a beam of sunlight through a prism in in order to produce a refracted spectrum of light that was then caught against (projected onto) a white screen. A beam of light so treated creates a spectrum instead of a beam, because the different colours which make up white light all have different wavelengths or frequencies, meaning they all bend by different amounts thus not landing on the same spot on the background screen. Hence a beam when refracted, causes not a beam but an expanded spectrum. When Wollaston created a spectrum of sunlight in this way, he saw in addition to the rainbow like colours of the spectrum itself, five dark lines and two faint lines (which Wollaston called shadows). He mistakenly assumed that they were the borders distinguishing where each of the four colours - red, yellowish green, blue and violet - ended and the other started.

Twelve years later in 1814, 27 year old Fraunhofer was bent on perfecting the accuracy of achromatic (distortion free) telescopes to provide superior image quality. To that end, he had been conducting experiments trying to isolate single colours allowing him to test each colour against each type of glass! His aim wast to: "measure for every kind of glass the dispersion of every color; but the different colours in the spectrum have no definite limits, and so this cannot be determined immediately...." Being a master lens maker proved to be a huge advantage in what came next. When he first tried to view a beam of light from a lamp through a prism he had noticed a bright yellow/red spot in the colour spectrum when seen against the screen. He wanted to know if sunlight would produce the same spectrum with the accompanying bright mark. Due to the superior equipment at his disposal, when he conducted his experiment, to his amazement, he realized that sunlight behaved differently. Instead of a bright spot at that point in the spectrum, he saw many, many dark lines throughout the whole spectrum. Wanting to get a clearer view of what he was looking at, he then used the telescope to view the spectrum with greater detail than was possible with his eye alone. He stated the result thus: "...Instead of this, I saw with the telescope an almost countless number of strong wand weak vertical lines, which are, however, darker than the rest of the color image...." His mind was more adapted to interrogate and understand the true nature of what he was seeing than was Wollaston's twelve years earlier.

The strongest lines do not in any way mark the limit of various colours. There is almost always the same colour on both sides of the line, and the passage from colour into another cannot be noted" Joseph von Fraunhofer

The statement: "There is almost always the same colour on both sides of the line," shows why Wollaston had previously come to the wrong conclusion. Whereas he thought the dark lines marked where each colour stopped and the next started, Fraunhofer saw that the background colour was on both sides of the dark lines, hence the dark lines had nothing to do with the spectrum. They must have been an additional type of information. He then created a chart of the highest precision to catalogue his findings. This included labeling the thicker lines with capital letters and counting more than 540 lines throughout the spectrum. Wanting to see if the findings of his detailed chart held true for other sources of celestial light or were they somehow a property of sunlight alone. Choosing Venus as his next source of light he studied the spectrum of it's light and found it to have the same lines as found in the sun's spectrum. Next, he tried the stars and found variation. How much variation? Why each star had different lines in its spectrum.

...I have seen with certainty in the spectrum of Sirius three broad bands which appear to have no connection with those of sunlight: one of these bands is in the green, two are in the blue. In the spectra of other fixed stars...these bands seem to differ among themselves"

That is, not only where the spectra of other stars all different from the sun's spectrum, they were different from each other as well. Having thoroughly demonstrated to himself through precise experimentation and multiple attempts using different methods, he, through logical reasoning, came to the only fitting conclusion:

I have convinced myself by many experiments and by varying methods that these lines and bands are due to the nature of sunlight, and do not arise from diffraction, illusion, etc" Joseph von Fraunhofer

Having a truly scientific disposition, he never lacked the vigour to pursue matters to the logical conclusions. After having finished his series of experiments with the stars, he returned to the original lamplight experiment to try and discern what caused the bright lines he had seen when the diffracted light was viewed against the backdrop of a screen. This time he viewed the resulting spectrum through his telescope and saw the bright yellow/red spot in the spectrum was in his words: "two very fine and bright lines, which in distance and intensity apart are like the dark lines D," in the spectrum of sunlight. In other words the spectrum of sunlight had the same two distinct lines on it, but they were black in that spectrum. What was going on? Another perspective paradox - something we can see, but not yet explain! This puzzle would not be solved in Fraunhofer's lifetime as he died prematurely from exposure to the fumes that heavy metals produce in the manufacture of his exquisite lenses. The same cause of death for his father, who had also been a lens manufacturer!

Dead at 39 years old, at his funeral, his mentor and boss, Joseph Utzschneider, announced the epitaph: "Approximativit Sidera," which translates to the English "He Brought the Stars Closer". Utzschneider, was of course referring to what have come to be known as Fraunhofer lines, which together with the classification lettering that Joseph von Fraunhofer invented more than two hundred years ago are still the standard in spectroscopy today. Among the honours he received in his short life was being appointed a Royal professor and being knighted in 1824. His epitaph would prove to be an understatement if ever there was one. For his returning to the lamp light and comparing it through a telescope with the spectrum of sunlight would prove to be his greatest contribution to understanding the stars, though no one - including Fraunhofer himself understood that truth at the time! His momentous invention - spectroscopy - would grow to have valuable uses in chemistry, astronomy, and physics. It would prove to be the most valuable tool in an astronomers toolbox!

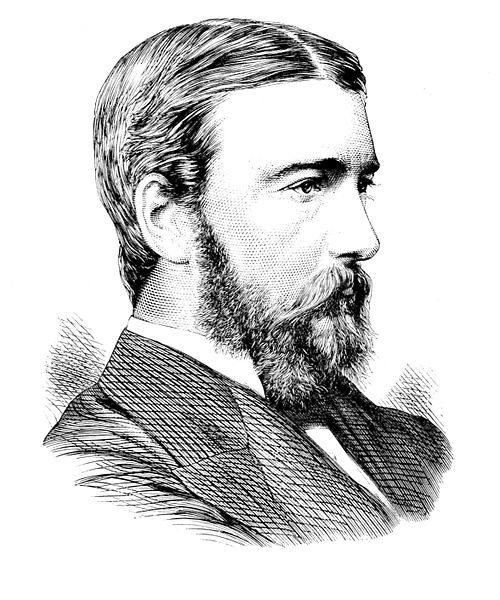

Balfour Stewart & Radiative Heat Transfer

An under appreciated physicist of the highest order was a man named Balfour Stewart (1 November 1828 - 19 December 1887). Having earned a degree in Physics from the University of Edinburgh, he started work as the assistant of James David Forbes, himself renowned for inventing the seismometer in 1842. Mr Forbes' main areas of interest were the investigation of heat, meteorology and terrestrial magnetism. Heavily influenced, Stewart similarly dedicated himself to solving the tangled mysteries of those fields. His success in cracking the paradoxes of heat and radiation were based on improving upon the foundations laid by Pierre Prevost in his "Law of Exchanges." His Wikipedia profile shows how he managed to:

... establish the fact that radiation is not a surface phenomenon, but takes place throughout the interior of the radiating body, and that the radiative and absorptive powers of a substance must be equal, not only for the radiation as a whole, but also for every constituent of it.Balfour Stewart - Wikipedia

Some scientists make their mark at the end of their lives, and others at the beginning. Of all his accomplishments, the greatest contribution Balfour made was to his very first investigation, which was into the nature of heat and radiation. The stunning insight had to do more with radiation than heat, and we will only understand it's impact fully at the end. Scientists still do not appreciate it true meaning. His discovery is summarized by his Wikipedia page, which states that he established: "the fact that radiation is not a surface phenomenon, but takes place throughout the interior of the radiating body, and that the radiative and absorptive powers of a substance must be equal, not only for the radiation as a whole, but also for every constituent of it." Now the fact that "radiation ... takes place throughout the interior of the radiating body," does not mean that light, is emitted inside of a radiating body. As we learnt earlier: no emission of radiation takes place inside of a radiating body. Rather what the text means is that through the various degrees of freedom, all the atoms or molecules inside a radiating body are participating in producing the final output of thermal radiation. Our focus though, is on something else: "the radiative and absorptive powers of a substance must be equal, not only for the radiation as a whole, but also for every constituent of it." It is this gem of a finding, that we will polish and shine some light on in a further chapter.

The Basics of the Different Types of Heat Transfer

To understand heat transfer we must have a thorough grasp of how object interact with energy. More specifically, how the atoms that make up objects interact with light. When light hits an object, the object can respond in one of three ways depending on its properties. It can absorb the photon of light. It can reflect it, or allow it go through it. These three processes are called absorptivity, transmissivity, and reflectivity respectively. Stating these relationships in a mathematical form, we get the straightforward equation: Total Incoming Light = Absorbed Light + Reflected Light + Transmitted Light. Mathematicians like to make things seem harder than they are. It is the symbols they use, which cause confusion, not the ideas that represent the reality. The reality is common sense to all of us since we live with everyday. Nonetheless, the symbols used to define the above equation are: Let's take it step by step. Since the are different three different things that can happen to the incoming photons, what we want is to know the ratio of how they relate to each other. That is, we want to know of all the incoming light, how much of it is absorbed versus how much is reflected, versus how much is transmitted (allowed to go straight through the material). To get that ratio we must divide the all the terms by the total incoming light. It is these ratios that we call Absorptivity, Reflectivity and Transmissivity. Our process written out in full looks like this: Anything divided by itself is...? One. Hence, we get 1 = Absorptivity + Reflectivity + Transmissivity. Remember, each of these terms is the ratio we get when we divide each of the only 3 possibilities that can happen to an incoming photon by the total amount of incoming photons. To the eight year olds. the number 1 on the left hand side of the equation, means 100%, which means all the things on the right must be a certain amount out of 100%. Simple right? And it never gets more complicated than that! From here we must just use common sense to figure out what is true. Here is the link to the excellent video explaining heat transfer, by Dr PM Robitaille:

Here is how mathematicians represent this formula in a shortened version: 1 = &v + pv = Tv. In math's since, different things are discovered by different people at different times, the symbols are hardly ever coordinated. The sign that looks like half of infinity stands for absorptivity. The sign that looks like a stylized 'p' represents reflectivity. The symbol for transmissivity at least looks more familiar: it like a capital 't' - and is called Tau. Now, let's restate our equation and play around with it, so we can clearly come to understand how it works band what it means: 1 = &v + pv + Tv. If absorptivity equals 1, meaning all the incoming photons are absorbed, then the other two terms must be 0, so that the equation balances. That looks like this: 1 = 1 + 0 + 0. The same is true if any of the other terms are 1. If 1 = 0 + 1 + 0, it means 0% of the incoming light was absorbed, 100% was reflected, and 0% was transmitted.

We continue with our thought experiment by adding more heat. What will happen. An ideal solid has a perculiar property unique to just them. The total amount of light they will emit is equal to their temperature to the power of 4. That means their temperature multiplied by itself 4 times. No ideal solids exist in nature. The closest material to an ideal solid is graphite. This characteristic of the thermal radiation of ideal solids is known as Stefan's law. However as much thermal radiation as Stefan's law allows our ideal solid to dissipate to its surroundings, there is a limit. As we pass that limit our solid must do something else in order to be able to handle the excess energy. As more heat is added, our solid will start to break the bonds holding its atoms together. This allows for 2 more degrees of freedom to become available, they are known as the translational and the rotational degrees of freedom. What does that mean? When the atoms where held together they could only vibrate back and forth about a central position along the axis of their chemical bonds, with their chemical bonds acting as the springs that accomplished that motion. But they could not turn around, for instance as their chemical bonds held them in place. Now that they are free of their chemical bonds, they can rotate and in place, or move from place to place. This last degree of freedom - translational motion, means that our solid can now accomplish both the flow of heat and mass, as atoms have mass.

Since the internal structure of our ideal solid is now changing, there must be a corresponding change in its phase. It can no longer stay as a solid, since its atomic bonds have been broken, it must phase transition into one of two other states: it can melt into a liquid state; or sublime into a gas. Graphite, for instance has no liquid form. It exists only as a solid, or a liquid. The phase transition from a solid to a gas is called sublimation. Since our ideal material is no longer in its solid state, we classify the energy held between its bonds as 0 (Ebond —> 0). We will not consider solids that sublime, as we want to study and understand all three phases of matter. Hence, we next consider what happens when we add more heat to our ideal solid as it melting into its liquid state. The first thing to understand is that between phase transitions, all heat goes to breaking the chemical bonds between atoms or molecules and none goes to increasing the temperature. Put another way while an element or substance is phase transitioning, it's temperature remains constant! So we understand that while phase transitioning, all additional heat goes not into increasing the temperature, but into finishing the phase transition, and the temperature holds steady. Only after the phase transition (melting or sublimation) is complete will additional heat have the effect of once again increasing temperature. Crash Course, the informative YouTube educational channel has produced a great video that explains phase transitions. It is entitled: The Physics of Heat: Crash Course Physics #22. The point at which phase transition takes place has a name. For solids changing into gases its called a melting point. When a liquid changes into a gas it's called a boiling point. Though it should be obvious from the definition, I will add for extra clarity these points represent unique tipping points. The term melting is only applied to describe a solid phase transitioning into a liquid. Similarly, a boiling point represents the phase transition between a liquid and a gas. You cannot have a boiling point between a solid and a gas, for instance. Nor can an element or substance experience multiple melting or boiling points. Once an element has gone through its melting point, if we continue to add heat its next phase transition threshold will be a boiling point and not another melting point. As obvious as that sounds, it is through these obvious points, that errors creep in.

You will start to notice a pattern. As elements go from the lattice structure of a solid to less and less tightly confined internal arrangements by gaining more and more degrees of freedom, the ratio of heat transfer that is accomplished by flow of heat lessens, as more and more heat is transferred through flow of mass. Understanding this point is critical. So critical, that it is actually the definition of phase transitions. Elements only gain degrees of freedom in response to their need to handle heat! When additional degrees are introduced, it has a limiting affect on the previous methods used by the element to handle heat. A case in point. When many solids turn into liquids, their earlier methods of handling heat dissipation have a smaller and smaller role as additional degrees of freedom come into play, often by a 100 times or more. Robitaille explains this new dynamic clearly, stating that after melting:

The requirements placed on conduction and radiative emission for heat dissipation have now been relaxed for the liquid and, mass transfer becomes a key means of dissipating heat within such an object. Indeed, internal convection, the physical displacement (or flow) of atoms or molecules, can now assist thermal conduction in the process of trying to reach internal thermal equilibrium. Convection is a direct result of the arrival of the translational degrees of freedom" PM Robitaille

In other words, the only means of heat dissipation in a solid - conduction and emission of radiation - now have another method to try and deal with the heat being introduced into the element, namely convection: the movement (flow) of atoms within the element from one place to another instead of the old 'conduction,' which was the vibrational movement of atoms around a central fixed point. Fixed, because the atom was tied to other atoms in a lattice. To restate this important point in another way, each phase of an element has degrees of freedom which are natural to it alone. When only those degrees of freedom are at play, they carry the whole load, but as the element gets more and more heated and undergoes phase transitions, additional degrees of freedom are introduced and as they become available they take the baton and start carrying the majority of the workload of dissipating heat, meaning the original degrees of freedom have a smaller and smaller ratio in the overall workload of transferring heat out of the element. To summarize, our liquid now has three ways to try and reach thermal equilibrium: conduction, convection and radiation. Conduction and convection work internally and radiation is always, always external. Remember, the whole point of radiating is to try and cool the element by getting rid of extra heat! It would thus make no sense if elements EVER radiated internally. The heat energy to be discarded must be thrown out of the element (system).

We must also keep track of what is doing what in our new liquid. Degrees of freedom do not change their dynamics with the addition of new degrees of freedom, nor do they swap functions once new degrees of freedoms are introduced. Each degree of freedom has a definite range of ways in which it, and it alone takes care of heat in the system. For example, the same degree of freedom which was responsible for conduction and thermal radiation in the solid is still the one responsible for it in the liquid. That was the vibrational degree of freedom, if you remember correctly. Similarly, the translational and rotational degrees of freedom are the ones that use convection to try and handle the heat in the system. You can separate conduction (which goes with radiation) and convection in your mind by thinking of the atoms in conduction as being like an orchestra 'conductor': he is free move (vibrate) his hands, but he must stay in a central position. Convection is like a 'conveyor' belt, it has translational (straight line) and rotational movement (as it comes back around). That is how the atoms use convection to move around and around in the liquid. Lastly, let's recap how the heat present in liquid is now divided: Evib + Etrans + Erot. At this point I again quote from Robitaille:

Very little is known regarding thermal emission from liquids. However, it appears that when confronted with increased inflow of heat, the liquid responds in a very different way. Indeed, this is seen in its thermal emission. Thus, while thermal emission in the solid increased with the fourth power of the temperature, thermal emissivity in a liquid increases little, if at all, with temperature. Indeed, total thermal emission may actually decrease. Stefan’s law does not hold in a liquid. That is because new degrees of freedom, namely the translational and rotational degrees of freedom (and its associated convection), have now been introduced into the problem. Since the vibrational degrees of freedom are no longer exclusively in control of the situation, Stefan’s law fails.... One can only surmise that convection rapidly becomes a dominant means of dealing with heat transfer in the liquid phase" PM Robitaille

What we can say is that the regular lattice of the solid gives way to a more irregular lattice in the liquid - but it is still a lattice. The difference is that in the liquid, it is fleeting. the bonds get broken and re-established based on the convection currents. The higherthe temperature of the liquid the lower its viscosity (loosely defined as its thickness). This shows that as more and more heat is introduced, there are more and more bonds broken, so the liquid flows more and more easily! We soon reach another temperature threshold. Eventually the three degrees of freedom will be unable to cope. This tipping point - the boiling point - brings about our second phase transition into our third phase of matter - the gaseous state. You may be asking: "what new degrees of freedom will uncover next?" As it turns out, degrees of freedom decrease in the gaseous state! Again, as while the element phase transitions from liquid to gas, the temperature remains constant even though heat is being continually added. Temperatures do not rise during phase transitions. As thermal radiation decreased by 100 times or more (in most elements) when we transitioned from solid to liquid, now thermal conduction decreases by more than 10 times as our liquid transitions into a gas. Those two dynamics make up our vibrational degree of freedom. So again we see the pattern that with each new phase transition, the oldest degrees of freedom have less of a role to play. In fact, the total amount of radiation emitted for a gas at constant pressure goes down rapidly as the temperature increases ! Since gases do not have a lattice structure, their atoms move freely. As such, the slack from the diminishing influence of vibrational degrees of freedom is picked up by the increase in the rotational and translational degrees of freedom.

Any increase in heat for elements in a gaseous state goes into increasing the kinetic energy of its lattice-free atoms. The atoms move around the gas freely at ever faster speeds. If our gas is a compound substance - made from two or more elements - then the additional heat will eventually lead to dissolving the compound into its constituent parts: the two or more elements that made up the compound. For instance, if the gas we're heating up is water vapour, then the H2O molecule will dissolve into two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom. Adding still more heat will then make the hydrogen and oxygen atoms move faster and faster within the gas. At this point, we introduce the dynamic of electronic transitions within each atom. Electronic transitions are where the electrons are excited by incoming energy and move to higher and higher orbital energy states. As the electrons move up and down these different energy states, they are absorbing and emitting light radiation. This is how the absorption and emission lines of elements are generated. Water dissolves elements or substances into a solution, but heat dissolves substances into the individual elements. That is an important distinction! Since the ability to emit radiation goes down in liquids and gases, compared to solids, we recognize that Stefan's law (radiation is equal to the fourth power of the temperature) does not apply to liquids and gases. Gases respond in other ways to excess heat energy, namely breaking apart any and all molecular bonds and leaving only elements - the constituent parts. This is why solids and liquids generate continuous thermal spectra when they radiate light, while gases generate either emission or absorption spectral lines through which their elemental identities can be ascertained.

There is one last phase of matter beyond gas - plasma. Again, nature follows the same rules, we add heat to the gas and when the electronic transitions within the gas atoms can no longer accommodate the excess heat, the gas phase transitions. During the phase transition the temperature of the gas does not increase, until all atoms have phase transitioned. What does this phase transition look like? As all we have left now are the bare atoms, and the phase transition was initiated and completed because the electrons had reached their limit of electronic transition, the next weakest bond in the atom is the bond keeping the atoms in their orbits so as we keep increasing the heat, the electrons themselves break free from the atom and become free floating electrons alongside positively charged nuclei (positively charged as they have lost negatively charged electrons). A non neutral atom that has either fewer or more electrons than it takes to make it neutral is called an ion, hence this process of turning gases into plasmas is called ionization. Its reverse: turning a plasma into a gas is called recombination!

We have gone through a relatively easy part of our discussion in great detail and with a lot of repitition, but do not lose focus Danielson, your working hard now to understand the basics will reap rich rewards very soon. Your mastering the: "wax on, wax off" tediousness of basic scientific knowledge, will soon prove invaluable to your clear understanding of what you may have previously thought were complex, bewildering subjects - once we start debunking them. God created the heavens and the earth, within the ambient temperature of the thermal limits of liquid water, that is the ambient temperature was between 0 to 100 degrees celsius. So, uncovering of the truths behind reality also falls within that slim range. Hence, all we need to have is a firm grip of the basics! As Denzel said: "It's the little things Jimmy... it's the little things that catch you." Understanding the basics and then paying close attention while you apply them honestly, are the keys to exposing the suppressed truths about the universe.

The The Law of Exchanges was a masterful accomplishment and though he would soon be eclipsed by our next scientist, in the end it was his findings and not those of Gustav Kirchhoff that would prove fundamental, as we will soon see. It is crucial to point out that radiation happens in the atoms of a material, but the direction of the radiation itself is external. Though it may seem obvious, it is important to note that the light produced by radiative processes is expelled out and not inwards. Processes of internal heat change are called convection and conduction. Radiation is external heat transfer - that's why hot objects glow. This will become important later.

The formulation of the Law of Exchanges is critical to understanding what will come later, so we must here give it proper attention. It is the simplest of all reasoning. Beautiful, in both its logic and simplicity. First we state the equation and then explain it's terms and the reality behind their logic.

Interestingly, by his time, less than two centuries after Newton, Stewart felt the need to co-author a book entitled Unseen Universe, the purpose of which was to combat - what had by then become - the conventional wisdom, that science and the Bible were incompatible. Sound familiar? Due to the heavy price that came with resisting such views, he initially published his book anonymously.

Understanding Heat Transfer in, and Phase Transitions Between Solids, Liquids and Gases

The explanation of Heat transfer and phase transitions was a not a part of Balfour Stewart's contribution to Physics, nevertheless, such explanations fit most naturally in this section of our discussion and are critical to enabling us to arrive at the truth of reality later on. The truth about the universe is that it is simple. It is people, wanting a pretext to be celebrated and honoured beyond their actual accomplishments who complicate it. First we tackle heat transfer in solids, liquids and gases. Again this section is based on the excellent work done by PM Robitaille, this time in his fantastically simple to understand paper: The Little Heat Ending: Heat Transfer in Solids, Liquids and Gases. In it, Robitaille explains the process of heat transfer by describing what happens to a solid substance as more and more heat is added to it. Of course heat is a form of energy, so this exercise is an understanding of how things work in our everyday lives. In solids, atoms are arranged in a regular, repeating manner called a lattice. Take note of that word as we will refer to it often. The only a solid has to respond to its absorption of heat is for its electrons to move. The different ways in which electrons can move are known as degrees of freedom. Initially our solid only has 1 degrees of freedom. We will start our thought experiment with our solid being at 0 Kelvin, that is absolute zero, or -273 degrees celsius. Substances can only approach absolute zero, but not reach it, as they must always have little bit of heat in them. If we add heat to such a solid, where does it go? This is where our degrees of freedom, come in. This of a degree of freedom as a "receptacle" that accepts the heat. The first degrees of freedom where the heat can go are always the vibrations of the atoms, either side of the absolute location. That means, although our atoms are now moving, their movement is back and forth around a central position, such that the absolute position stays the same. At this early stage, the solid is trying to reach thermal equilibrium, which means it is trying to spread the heat evenly between all its atoms. Robitaille paints a clear picture of this process for us when he states:

Thermal conduction is the process whereby heat energy is transferred within an object without the absolute displacement of atoms or molecules" PM Robitaille

Yet, even though our solid is trying to reach thermal equilibrium through conduction, it will not be able to because another process will kick in to help get rid of (dissipate) the heat into its surroundings - giving off light! To summarize, as a substance gets heated, it will first start moving its atoms vibrationally. However, not all of the heat energy that is captured in these vibrational degrees of freedom will be conducted until all the atoms share this heat energy equally. Before that process is complete, some of the heat will escape the solid as radiation - light. Since this light was emitted to try and cool down our object, it is called thermal (heat) radiation (light). Such light is emitted at different frequencies. And so, in addition to the 1 degrees of vibrational freedom, emission of light is another way objects have of dealing with heat. In the meantime, something interesting has happened. The energy that escaped our object is now no longer part of the object, but of its surroundings. So to summarize our object's total energy is Esolid = Erest + Evib. On the other hand Etotal = Esolid + Eem, which takes both the solid and it's environment into account.

Norman Lockyer

In 1861, Norman Lockyer (17 May 1836 - 16 August 1920) was 25 years old and not yet officially involved in the field that would lead him to fame and wide acclaim. Though working as a civil servant for the War Office in Wimbledon, England, his keenest interests were in the stars. Lockyer was an avid amateur astronomer, and was particularly taken with studying the sun. Hence, when he met and befriended a lens maker in 1862, named Thomas Cooke who manufactured Lockyer a 6 and quarter inch lens, he was quick to build a DIY enclosure with the combined parts acting as Lockyer's telescope to study the sun. You can imagine his delight when, thus setup, he learned of spectroscopy and its uses in studying the sun.

How did Lockyer know that the red ring around the sun must be in a gaseous state? Why did he have to go to all the trouble of inventing a new type of telescope to isolate their spectrum? What difference was there between the nature of their spectrum and the spectrum of the rest of the sun, so that his technique for isolating their spectrum would work on the them, but "block out the rest of the brilliance of the Sun?" No one who glosses over these questions will ever acquire a full understanding of the Science of Spectroscopy - and more importantly: of reality!

With his attention growing towards astronomy, Lockyer was now making friends within the community of scientists that was involved in astronomy. One of these was Balfour Stewart. Stewart had a theory about the true nature of sunspots that is not integral to our discussion, with its only import being that it provided Lockyer with the chance to prove Stewart correct in with empirical evidence. This his duly did in March of 1866, through his rapidly accumulating mastery of spectroscopy! Having settled what had been a vigorous debate among scientists, Lockyer and Stewart - closely allied in their approach to astronomy - revisited an earlier problem they had struggled with and wondered how spectroscopy could help in cracking what seemed to be an intractable problem: the nature of the red flames visible in the corona in solar eclipses. In previous solar eclipses, at the moment of full eclipse when light from the core of the sun was blocked, the corona became clearly visible and with it the glimpse of mighty red flames of differing heights right at the boundary of the darkened solar disc. Because they were

To do so, Lockyer theorized that he would have to point his spectroscope at the edges of the sun, where the red flames had been seen. Of course, when he tried he could not find any evidence for the red flames, not matter how diligently he tried. The problem in his own words was the:

...excessive brilliancy of the spectrum of the circumsolar regions in the field of view of the instrument I employed" Norman Lockyer

His central problem then was how to recreate the conditions of a solar eclipse without having to wait for one. Fortunately, Lockyer had an inventive mind and endless resourcefulness. Having proven his scientific virtues with his validation of Stewart's sunspots theory, he applied to the English government for aid in building a unique telescope. Recall that spectroscopy is the science of identifying elements through their emission or absorption lines as first practiced by Bunsen and Kirchhoff, who then quickly applied it the sun after he recognized the connection with Fraunhofer lines. For spectroscopy to the work, the substances in the atmosphere of the sun had to gaseous. Building on that foundation, Lockyer and Stewart had concluded that red flames seen in the sun's corona since they were more brilliant than the corona itself, must also be gaseous in nature. Herein lay the solution to his tricky problem with isolating them outside of the window of solar eclipses. I quote him to make the point clear. had concluded that

The light from solid or liquid bodies, as you all I am sure know, is scattered broadcast, so to speak, by the prism into a long band of light, called a continuous spectrum, because from one end of it to the other the light is persistent" Norman Lockyer

It is this variability that Lockyer was determined to find a way to exploit. His solution was both simple and ingenious. The light studied spectroscopy must must first be isolated (by being passed through a slit for instance) before it is aimed at the prism. It then exits the prism having been dispersed. Taking a set amount of light and dispersing it has the effect of also weakening or dimming the resultant light that is now in the form of a spectrum. That much is obvious as you have the same amount of light covering a wider area, in the form of the spectrum. However the light from gases does not behave that way. Instead, the emission or absorption lines of gases are focused at particular frequencies and come in the form of rigid spectral lines. The solution then would involve accentuating the effect of the dispersion of the continuous spectrum of the body of the sun, making it dimmer and dimmer until the gaseous spectral fingerprints would be perceptible within. "Excessive brilliancy of the spectrum of the circumsolar regions" was the problem, and Lockyer had found the way to dim that brilliancy. The instrument to magnify the dispersion was already at hand - the prism. How would amplify its effect. Not by making it larger but by passing the original light rays through successive prisms, each dispersing the original white light into a broader and broader, and thus dimmer and dimmer spectrum. His final design was a seven prism spectroscope, it was delivered to him on the 16th of October 1868.

My first attempts, however, with the new instrument, not yet in adjustment, were as unsuccessful as those made with the smaller one; and it was not till the 20th of October that, after sweeping for about an hour round the limb and arriving at the vertex of the image, near the south pole of the sun, I saw a bright line flash into the field. My eye was so fatigued at the time that I at first doubted its evidence, although, unconsciously, I exclaimed 'at last!' ...Leaving the telescope... I quitted the observatory to fetch my wife to endorse my observation" Norman Lockyer

Success! Though creative, the solution to being able to study the corona outside of solar eclipses was not rocket science. It was starring Lockyer in the face due to the known facts about the differences between the thermal spectra of solids and liquids versus gases as discovered by Bunsen. So logical was the solution, that it was the exact same one arrived upon by another astronomer Jules Janssen, who having witnessed the solar eclipse in person, two days later came up with a multi-prism spectroscope as the logical answer to dimming the brilliancy of the sun and thus being able to study the corona outside of solar eclipses. Lockyer had identified three spectral lines from his "sweeping" search of October 20. Persisting with his work, he in December of the same year discovered a fourth line. When he tried to identify the elements which made these lines, it was clear that hydrogen was one of the elements as its spectral signature fit perfectly. However, there was one line, which was very close but didn't quite match and no element in the catalogue of known elements fit its profile. More than that it was not even predicted to exist and no evidence of it could be found on earth! Undeterred, and having diligently ruled out that it could not be some as yet unknown form of Hydrogen, Lockyer named it after the Greek mythological god of the Sun Helios, and so was born Helium! Helium was the first element to be discovered in space before it was verified on earth! Why? Because its discoverer knew the basics of spectroscopy and used those principles to intelligently find a solution to an otherwise troublesome problem. Helium is evidence of the regression of science. How is it, that 153 years after, as Lockyer put it: "The light from solid or liquid bodies, as you all I am sure know, is scattered broadcast, so to speak, by the prism into a long band of light, called a continuous spectrum, because from one end of it to the other the light is persistent," that scientists now claim that the sun and stars are gaseous when they only produces continuous spectra?

Honours

The craters Lockyer on both the Moon and Mars are both named after him, among several other honours.

Gustav Kirchhoff

Gustav Robert Kirchhoff (12 March 1824 - 17 October 1887) was a highly gifted German physicist who contributed to many fields of scientific research. It was Kirchhoff who coined the term blackbody radiation in 1862, but first we must start with the time he met Robert Bunsen (30 March 1811 - 16 August 1899) - a German chemist of the highest order. At 24 years old and with a scholarship to study in France, Kirchhoff was traveling through Europe, but found his progress arrested by a revolution in 1848. With this change of plans, he made the best out of a bad situation by instead negotiating a professorship for himself at the University of Breslau. It was here that he first met and became fast friends with Bunsen. Four years after that Bunsen earned himself a chemistry position at the prestigious University of Heidelberg. Being a prominent scientist, he was then able to help secure a position for his friend Kirchhoff in the Physics department of the University.

Of all the men of Science, who were prone to deviation from the scientific method, perhaps none have embraced - or embodied, depending on motivation - the role more fully than Gustav Robert Kirchhoff. Never has true Science suffered more from its corruption and degradation than under the influence and guiding hand of Kirchhoff. Was it his intent to mislead, was he himself misled, and therefore more victim that perpetrator? We won't know for a while. What is certain, is that the corruption of Science can clearly be traced to his inept researches, conducted with an incoherence that borders on malice and willful deception.

A few years into their respective tenures, Bunsen in his own experiments realized that the gas burners of his day were inadequate for his chemical experiments, they didn't produce a hot enough flame. Being the inventive man he was, in 1857 he came up with the Bunsen burner, a staple in chemistry classrooms to this day. With good experimental equipment now at hand, he decided to intelligently study the light of different chemical salts. These experiments used filters to study the light, but were not very effective in producing the best results. Finally, in 1859 Kirchhoff learned about the difficulties Bunsen was having with his experiments, and, having a rich background in Physics, where physicists had long been studying light quite effectively through prisms. However, there was a spanner in the works. Physicists had a problem. When they looked at sunlight through a prism, white light was divided into a rainbow of differently coloured light that sat beside each other as each colour of light bent by a different amount (degrees), creating a spectrum. But when the same experiment was performed with light from heated gases, they got not a spectrum, but rather sharp lines of different colours against a black background - a genuine perspective paradox! To further their now joint experiments, Kirchhoff suggested they use a prism attached to an apparatus adapted to allow them to study different gases. They would then compare the results systematically to try and understand what was going on. The result? Each element produced different variations of that same theme coloured lines against a black backdrop, but while the background was always black, each elemental gas produced different colours of lines at different places. In the end when they compiled their results they discovered that each element had its own fingerprint: its prism signature was different for all other elements. Of course, we know this was because of our discussion about light and how it is produced when electrons absorb and emit different packets of energy - quanta. Each element can only interact with very specific quanta and no two elements have the same profile of quanta. Since these quanta of energy are the wavelength of the electrons in the element and wavelength is the same as colour, each unique element in turn produces unique colours.

The two then moved on to compounds (a substance made of two or more elements). This helped them to identify compounds that had not yet been discovered. When they looked at the spectral lines produced by compounds, they would use their catalogue of individual spectra to separate the combined spectrum of compounds into its constituent parts and thereby easily identify what each compound material was composed of. Through these experiments, they managed to isolate two spectra which could not be matched to any currently known elements and thus discovered two new elements that they named Rubidium and Cesium, after the colours where their most prominent spectral lines appeared - red and blue parts of the spectrum respectively. Later that year, Kirchhoff was toying with different combinations when he came up with the idea of putting a lamp behind his burning gas, which happened to sodium. He knew that the lamp using a liquid as fuel would produce a continuous rainbow-like spectrum, as is the case with any solid or plasma gas heated to the relevant temperatures. His expectations with the addition of the sodium in front was that the result would be a background of the rainbow spectrum but with two highlighted bright yellow lines, but of course that is not what he got. To his great surprise he saw two sharp black lines where he expected the yellow lines to be! For the first time someone had managed to reproduce something that had the appearance of the sun's spectrum! Kirchhoff quickly realized the significance of his new discovery, since the sun had the exact same dark lines at exactly the same spot in its spectrum, it too must have sodium as one of its ingredients! This meant elements absorb and emit the exact same frequencies. The perspective paradox of the Fraunhofer lines had been solved. Discovering what else the sun was made of would now be a simple task of identifying the other element fingerprints in its spectrum.

It was shortly after this in July of 1860, that Kirchhoff came up with the name blackbody. His discovery about the nature of the sun and the spectral lines of its constituent elements was essentially a discovery about the relationship between heat and light in all matter! Having come to understand that all elements have a unique spectral fingerprint that identified them through the frequency(ies) of light they absorbed and emitted from a continuous spectrum, he theorized about the existence of a hypothetical object that could absorb and emit ALL frequencies and thus would emit not unique spectral lines but the whole continuous spectrum ITSELF! At this point, it is important to carefully try and understand the FULL implications of such an object! As it would emit a continuous spectrum, it would be impossible to identify what elements it was made of as no element on the periodic table has a continuous spectrum; they all have unique, discrete spectra due to the unique energy signatures that make one element different from another. Moreover it is not possible to combine the different elements in some way that when all their unique spectra are combined (superimposed), they form a continuous spectrum! For clarity, we must resolve to a higher resolution between the continuous spectrum of a body like the sun and the proposed continuous spectrum that a blackbody would produce (emit).

There is a difference between the continuous spectrum that the sun - through its plasma - and liquids and solids emit and the continuous spectrum of a hypothetical blackbody. The sun, liquids and solids can only produce a continuous spectrum at high temperatures due to the ionization of atoms and sometimes molecules. Hence, their continuous spectra are functions of their high temperatures and are not blackbodies! Much of scientific literature likes to make false distinctions between blackbodies and perfect blackbodies, but in truth, there is no such distinction. Its either your spectral profile identifies you as a blackbody or not! A second distinction is to realize that such an entity, were it to exist would be unique and you could not have two such substances in the universe. As we have already established, each element in the periodic table - when in its gaseous form - produces its own unique fingerprint: a spectral profile. Wherever, we encounter such a profile we can identify with certainty what that substance is because each fingerprint matches uniquely to only one element. We can never, BY DEFINITION, have a situation where there are two uniquely differing substances with the SAME spectral profile. A substance is defined by the atoms that make it up and the spectral signature of each element is what identifies which atoms those are! Similarly, if it were to exist, there could ONLY EVER BE ONE blackbody in the universe. This unique substance, would produce a continuous spectrum no matter what temperature it was at. The only difference raising or lowering the temperature would have was to determine at what portion of the electromagnetic spectrum it would peak at. However, the whole spectrum would be represented. That is what a blackbody is: a substance that absorbs and emits ALL frequencies of the electromagnetic spectrum! In a paper entitled On the Relation Between the Radiating and Absorbing Powers of Different Bodies for Light and Heat, Kirchhoff, theorized about just such an imaginary perfect object. He describes it as:

Why Plasma is Not a Fourth State of Matter

Ionization

There are three states of matter: solid, liquid and gaseous. When elements are in their denser solid and liquid states they produce continuous spectrum because individual atoms are having their electrons stripped by high temperatures creating a melting pot of many different frequencies, that meld together to produce a continuous spectrum. As the element continues to be heated it will undergo a phase transition from solid to liquid and later from liquid to gas. In such phase transitions the temperature only continues to rise once the phase transition is over. So a sold being heated will rise in temperature its melting point (the point at which elements phase transition from their solid to liquid states). It will then continue at this temperature until all of it has transitioned to the liquid. At this point the temperature will once again start to rise until it reaches its boiling point (the point at which elements phase transition from liquid to gas - again different for each element). Because the solid and liquid states represent the most dense states of matter, they produce continuous spectrum due the ionization caused by frequent collisions between their molecules. Gases are different. In gases molecules of atoms are more spread out causing fewer collisions. For this reason, when a gas is heated the discrete nature of its atomic structure is more readily apparent. Hence gases produce emission lines against a black drop. If a gas is heated in front of a solid or liquid, it will absorb the portion of the continuous spectrum produced by the solid or gas and thus form black absorption lines against the background of a continuous rainbow-like spectrum produced by the solid or liquid. Though, the sun is a gas, due to the immense pressure of its core is effectively mimics the dynamics of a dense liquid - a plasma. Due to their dense atomic structure solids, plasmas and liquids all emit continuous spectra.

The proof I am about to give of the law above stated, rests on the supposition that bodies can be imagined which, for infinitely small thicknesses, completely absorb all incident rays, and neither reflect nor transmit any. I shall call such bodies perfectly black, or, more briefly, black bodies." Gustav Kirchhoff

This was a profound insight as it meant, since it didn't reflect any light, then any light that it would emit would be from the body itself! Unlike, the moon for example which can only reflect light from other sources. The fact that such a body of infinitely small thickness would not "transit any" light means it no light would pass through it! A quick review of its proposed properties are it would not reflect any incoming light, like the moon; it would not transmit any incoming light, like the glass; it would absorb all incoming frequencies of light completely (hence its description as being: "perfectly black"); and it would emit the full electromagnetic spectrum. Take not that absorbing can happen with individual frequencies, but emission is never with individual frequencies but always an emission of the full electromagnetic spectrum! Thus he theoretically predicted that such light could only be the product of the temperature of the blackbody and the frequency. Again in his words:

The magnitude indicated by I is, as remarked in __5, a function of the temperature and the wavelength. The determination of this function is a problem of the highest importance; and though difficulties stand in the way of our effecting this by experiment, there is nevertheless a well-grounded hope of ultimate success, since the form of the function in question is no doubt simple, as is the case with all functions hitherto discovered that do not depend on the properties of individual bodies" Gustav Kirchhoff

Though the formula itself, did indeed prove to be simple in form, discovering it was anything but, as we will soon find out. What is important for now is that the resulting equation would be simple because it would not need to factor in the properties of the substance, only its temperature and relevant frequency. This independence between the function and the properties of the atomic structure of the blackbody is a second verification that receiving a spectrum from such a body would not tell us anything about the material itself - its structure. That is significant for reasons we will understand more clearly afterwards.

Defining the equation for blackbody radiation was a problem every physicist worth their reputations tried to solve over the next four decades, and its resolution would usher in a new and almost unimaginable era in physics. One that would forever alter mankind's perceptions of reality. The first to publish a proposed solution to the perplexing enigma was our next figure.

Josef Stefan

Stefan's law was a triumph. Our interest in it, is not limited to its role in establishing the empirical catalogue of knowledge found in the science of Thermodynamics, no, more important than that for us is that it is a physical law! In other words, it is a law that describes relationships between physical entities. The relevance of this rather obvious, yet subtle truth will be realized further on. For now, we just take a mental note of the fact! Josef Stefan's law: "the total radiation from a black body is proportional to the fourth power of its thermodynamic temperature T. "

Max Wien

Wilhelm Wien (13 January 1864 - 30 August 1928) was a German physicist who was the director of the Institute of Physics at the University of Jena, in Thuringia Germany. As his research focus was high frequency electronics, he was ideally qualified to attempt the challenge.

Defining the Ultra Violet Catastrophe

The simple equation Lambdapeak = 0.0029/T describes the relationship between the temperature of an element and its peak wavelength. Expressed in words, it simply says the wavelength of an element is inversely proportional to its temperature (an inverse relationship simply means when one goes up the other does down and vice versa). Understanding why is straightforward because the peak wavelength is in the numerator and the temperature is in the denominator, that tells you they do not vary in sync with, but opposite to each other. Let us illustrate with something we are more familiar with, regular numbers. If we say x = 2/10, we can calculate the answer: 0.2. If we were to increase 10 to 100, would the answer be smaller or larger than 0.2? It would have to smaller because of the position of the two variables, x is in the numerator and 100 is in the denominator. Since 100 is larger than 10, then the current answer for x must be smaller than 0.2, and it is: x now equals 0.02. In the same way the relationship between the peak wavelength and the temperature of a substance is inverse. When one goes up the other goes down, in this case by a factor of 0.0029, normally expressed as 2.9X103.

The reason we only need to consider the peak wavelength is that an element displays a unique spread of wavelengths for each unique temperature. Put another way, every time a particular element is at a certain temperature its spectrum of wavelengths will always look the same. This is true for all elements. Since, that is the case, we only need to identify one wavelength, which we will use to identify that whole spread of wavelengths. That determining wavelength is the peak wavelength. Each element has unique profiles, but those profiles are always the same for each unique temperature.

When this equation is plugged into the numbers in becomes obvious that the higher the temperature the smaller the wavelength (with wavelengths, the correct description is shorter or longer).

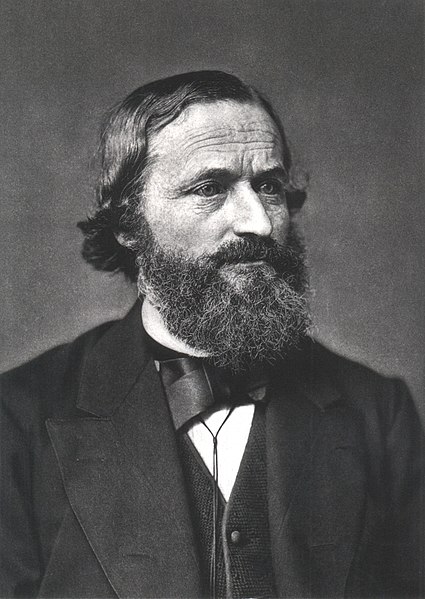

Max Planck

Max Planck, (23 April 1858 - 4 October 1947) was a natural genius, who would go on to redefine the world of physics almost without realizing it. Having completed his PhD in physics by the age of nineteen, he would go on to make many profound contributions to theoretical physics. His friend Wilhelm Wien had published an equation as a proposed solution to Kirchhoff's hypothetical blackbody enigma. It fit some of the data but not all, and to Planck's dissatisfaction, it was developed experimentally and not theoretically. The distinction is hugely important. Without an overarching theory that can give you the big picture of what is really happening, even a correct experimental solution only tells you the bare minimum about what is actually happening. To truly understand scientific phenomenon, one needs to know the theory that explains their reality! Planck was regarded - both by himself and others - as the best theoretician in Germany and so he took upon himself to work on Wien's law until he could imbue it with a firm theoretical framework. This proved to be no easy task, taking five years in total from the time Wien published his equations. In 1999 he was ready to publish he was ready to publish his own findings. He proposed it as a fine tuning of Wien's law.

For this reason on the very day I had formulated this law, I began to devote myself to the task of investing it with true meaning. For six years I had struggled with the black-body theory. I knew the problem was fundamental and I knew the answer. I had to find a theoretical explanation at any cost." Max Planck

Again, the ugly but necessary question of legacy comes up. In coming to a true assessment of a person's contributions to the human race, we must acknowledge, not only their positive contributions, but also factor in their negative impacts. Planck, being a German physicist in the time of Hitler, certainly had to face many difficult choices in his life, but none of those are the subject of our focus. The source of his negative impact starts with a following in the footsteps of Kirchhoff, and terminates in a sort of egotistical madness, that prompts men to try and bend scientific principles to their will, so that they may do their bidding! It is most unfortunate that a mind as great as Planck's succumbed to this basest of impulses in his search for glory. Robert Greene, in his book Power: The 48 Laws, tells the anecdote of Sir Christopher Wren, the most notable architect in England in his time. The story goes that: Having finished the plans of a town hall in Westminster, the mayor felt uncomfortable with the fact that there were no pillars holding up the extensive ceiling. Of course, Wren, master engineer that he was, was certain of the integrity of his structure, but the mayor insisted that the design was unsafe and Wren must amend it by adding two central pillars. Wren duly complied, but built the pillars to fall just shy of reaching the ceiling, a fact that could not be ascertained from the ground floor, as he knew that posterity would prove him right! In time, the fact would be discovered and the strength of his original design vindicated. It appears, that there are men who act with the opposite character, they bamboozle their contemporaries with theories that seem valid, but that they surely know will be disproven with time. Is acclaim so worthy a goal, that one would sacrifice integrity to attain it?